지난 15년 넘게, 나는 한국 영화와 관련해 수 천 통의 이메일을 받았다. 운영 중인 한국 영화 사이트가 쉽게 검색될 때 흔히 일어나는 일이긴 하다. 특별히 자주 오는 이메일의 유형은 다음과 같다. (a) 한국 영화 논문에 대한 도움이 필요한 대학생 (b) 팬이나 업계 종사자로서 특정한 영화감독(특히 김기덕)과 접촉을 하고 싶은 사람들 (c) 한국 영화계에서 일하고 싶은 외국인 또는 한국 제작자에게 극본을 보여주고 싶은 사람들.

최근 몇 년 동안 먹고 사는 일에 치여서 사이트에 시간을 덜 쏟았더니 ‘구글 랭킹’은 떨어졌고, 지금은 훨씬 적은 메일을 받고 있다. 사실 사이트에 아주 많은 공을 들이던 시절에도 내가 답할 수 있는 건 한계가 있었다. 그러나 내가 일 년에 한 두 번씩 계속 받는 특정한 유형이 있기에 늘 정성스럽게 답장을 쓰곤 한다.

지난 1월 LA에 사는 한국계 미국인으로부터 한 통의 이메일을 받았다. 자신의 어머니에 대한 이야기 였다. 1967년에 데뷔한 한국의 여배우였고, 신성일과 남진 같은 유명한 스타들과 여러 해 동안 함께 영화에 출연했다는 것이다. 그는 어머니가 찍은 영화가 몇 편인지 확실히 몰랐지만 일부라도 볼 방법이 있는지, 어머니의 선물로 DVD 복사본들을 구할 방법이 있는지 애쓰고 있었다. 한국말을 못했기 때문에 아무래도 애로사항이 많았다.

이런 요청에 나는 잠시 영화 평론가에서 사설 탐정으로 변신했다. 오래된 한국 영화 라면 한국영상자료원에서 운영하는 한국영화데이터베이스(KMDB, http://kmdb.or.kr/)가 항상 첫 번째 정보원인 법. ‘의뢰인’의 어머니가 1967년부터 1971년까지 11편의 영화에 출연했다는 사실을 알아냈다. 정보원(데이터베이스)은 필름이 여전히 존재하는지, 그리고 그렇다면, 어디서 그것을 감상할 수 있는지 알려준다.

내가 밝혀낸 진실은 수많은 과거 한국영화들, 심지어는 비교적 근래의 영화들까지 분실돼 왔다는 것이다. 그녀의 데뷔작을 포함해 아들이 특별히 찾고 싶어 했던 11편의 영화 중 5편이 완전히 사라졌다. 또 남은 6편의 영화 중 어떤 것도 DVD나 VHS로 출시되지 않았기에 복사본을 구매하는 것조차 불가능했다. 임권택의 덜 알려진 작품들을 포함해 3~4편 정도만 서울의 한국영상자료원 도서관에서 자막 없이 볼 수 있었다. 오직 한 편만을 캘리포니아에서 볼 수 있었는데 그녀가 스치듯 등장했던 영화인 신상옥 감독의 ‘내시’ 였다. 위대한 이 영화는 자막 없이 영상자료원(영상보관소)의 온라인 VOD 서비스에서 볼 수 있다. ‘내시’는 예전에 뉴욕의 MOMA 같은 곳에서 ‘신상옥 회고전’을 통해 몇 번 상영되기도 했다.

적어도 위와 같은 경우는 이메일을 보낸 사람에게 내가 뭔가 보여 줄 것이 있었던 사례다. 의뢰인들이 그토록 간절히 찾기 바랬던 영화가 더 이상 존재하지 않는다고 알려야 했던 적도 종종 있었다. 영화라는 게 영구적인 것처럼 보이지만, 이런 요청들을 통해서 얼마나 많은 한국 영화의 역사가 없어지고 있는지를 새삼 떠올리게 된다.

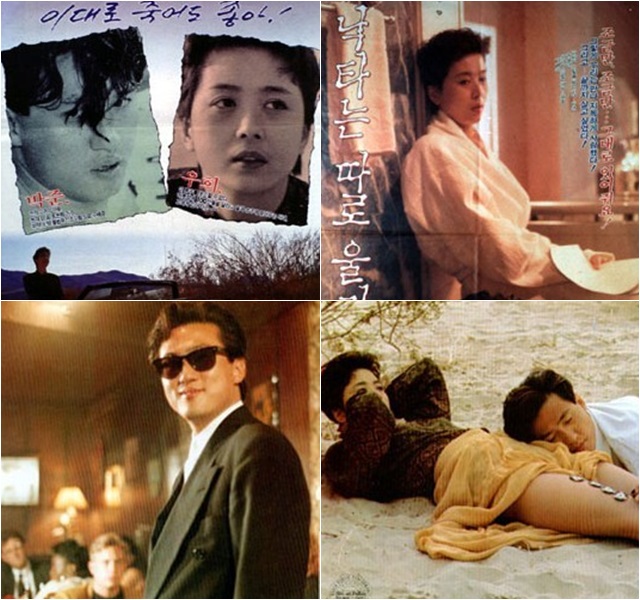

1990년대 같은 최근의 영화들조차도 볼 수 없는 경우가 있다. 지난주 미국의 한 여배우가 이혜숙- 손창민 주연의 ‘낙타는 따로 울지 않는다(1991)’를 찾는다는 메일을 보내왔다. 영화의 많은 부분이 샌프란시스코에서 촬영됐고, 그녀는 직접 출연했던 미국 배우 중 하나였다. 슬프게도, 그 영화의 필름 역시 사라졌다. 영상자료원이 상업적으로 생산된 VHS 테이프를 가지고 있었지만 말이다. 또다시 나는 나쁜 소식을 전해야 했다. 그러나 나는 몇 장의 스틸 사진을 찾을 수 있었고, 그녀에게 ‘다음(Daum) 영화’에 있는 배우 페이지를 보여줄 수 있었다. 만약 오래된 VHS 복사본을 팔고자 하는 독자가 있다면, www.koreanfilm.org을 통해서 내게 연락을 주면 좋겠다. 한국에선 잊혀진 영화일지 몰라도 제작에 관여한 많은 사람들에게는 큰 의미를 지닌 작품이기 때문이다.

영화평론가 겸 배우

<원문보기>

A Film Critic Becomes a Detective

Over the past 15 years, I have received thousands of emails about Korean film. That’s one thing that happens when you run a website on Korean cinema, and are easy to find on Google. There are several types of emails that have come particularly often: (a) university students looking for help with their research papers on Korean film; (b) people -- sometimes fans, sometimes people in the business -- who want to get in contact with a certain director (especially Kim Ki-duk); and (c)people from other countries who want to find work in the Korean film industry, or who have written a screenplay that they want to show to Korean producers.

In recent years, with a family to support, I’ve been able to spend less time on my website. So my Google rankings have dropped, and I get much fewer emails than I used to. Even when I was spending a lot of time on the website, there was a limit to how many of those emails I could answer. But there is one particular type of email that I continue to receive once or twice a year, that I always make a special effort to answer.

For example, in January a Korean-American man living in Los Angeles emailed me regarding his mother. She had been an actress in Korea, making her debut in 1967 and appearing over the years alongside famous stars like Shin Sung-il and Nam Jin. He wasn’t sure how many films she had made, but he was trying to find a way to watch some of them, or to get copies of them on DVD that he could give to her as a gift. He himself did not speak Korean, so he was having trouble making any progress.

For requests like this I have to transform briefly from a film critic into a kind of private detective. For information regarding older Korean films, the KMDB database (http://kmdb.or.kr/) run by the Korean Film Archive영상자료원 is always the first source to consult. I found that the man’s mother had appeared in 11 films between 1967 and 1971. The database also tells you if the film print still exists, and if so, where it is possible to watch it.

The truth is, a tremendous number of Korean films from the past ? even the fairly recent past ? have been lost. Of the 11 films, 5 had disappeared completely, including her film debut which he was particularly interested to find. Of the remaining 6 films, none had ever been released commercially on DVD or VHS, so it was not possible to buy copies of them. 3 or 4 of them, including a lesser known work by Im Kwon-taek, could be viewed without subtitles by visiting the Korean Film Archive’s library in Seoul. Only one film could be viewed from California: Shin Sang-ok’s Eunuch 내시, in which she had a brief appearance. This film (a great movie which I highly recommend) can be seen on the film archive’s online VOD service without subtitles, and there have been times in the past when the film has screened in Shin Sang-ok retrospectives, for example at MOMA in New York.

In this case at least, there was something I could show to the person who emailed me. There have been several other examples in the past when I had to inform an emailer that the film they so desperately wanted to find no longer existed. Film may look like a permanent medium, but requests like these are a reminder of just how much of Korea’s film history has been lost.

Even films made as recently as the 1990s can be inaccessible. Last week, an American actress emailed me looking for the Korean film Camels Don’t Cry 낙타는따로울지않는다 (1991) starring Lee Hye-sook and Son Chang-min. Much of the film had been shot in San Francisco, and she was one of the Americans who acted in it. Alas, the print for this film too has disappeared, although the film archive holds a commercially produced VHS tape. Once again, my email to her contained bad news, but I was able to find some stills from the film and show her her actor’s page in the Daum film database. If there’s any reader out there who has an old VHS copy of this film that they would be willing to sell, please contact me through www.koreanfilm.org. It’s a film that most people in Korea have forgotten, but which could mean a lot to the people who took part in making it.

달시 파켓 '대한민국에서 사는 법' ▶ 시리즈 모아보기

기사 URL이 복사되었습니다.

댓글0